“The Greatest Game Ever Played” shows modern golf’s beginnings

February 28, 2003

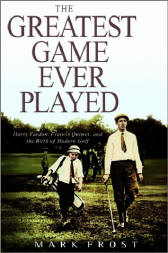

I recently finished one of the best golf books I have ever read–Mark Frost’s The Greatest Game Ever Played: Harry Vardon, Francis Ouimet, and the Birth of Modern Golf (Hyperion, $30 SRP).

It combines several elements in a seamless narrative that builds to a compelling finish, a feat not often accomplished when the basic facts are already well-known.

First, it’s a great sports story. Frost describes how Ouimet, a young former caddie barely out of his teens, manages his game to a highly unlikely but ultimately extremely popular victory in the 1913 U.S. Open. Ouimet and his plucky little caddie, Eddie Lowery, overcome all sorts of on- and off-course obstacles along the way to winning one of the most significant Opens in its first century of competition.

Second, the book is a well-written social history of America and Great Britain from the late nineteenth century and World War I. Frost outlines the growth of American golf along with the country, as it recovered from the Civil War and began to assert itself on the international stage. The concurrent changes in Great Britain and the continent are also well-done, putting the exploits of professional golfers on both sides of the Atlantic in their proper context.

Third, it’s a stirring biography of Harry Vardon, Francis Ouimet, and many others whose contributions to modern golf are hard to overstate. For example, Frost treats the readers to America’s first national experience with Walter Hagen’s career as a professional golfer, as a useful counterpoint to the path chosen by Ouimet, a true amateur.

Like Jack Nicklaus in his prime, Vardon played his own highly skilled game with a supernatural calm. He let his constant excellence be the weapon that dispirited his opposition and forced them to make mistakes. He rarely made errors himself, until a bout with tuberculosis injured portions of his nervous system. This caused a real case of yips around the putting green, which gave other players an opening they could and did exploit more successfully than before the attack.

Even so, in 1913 the middle-aged Vardon remained a significant force. With his friend and compatriot Ted Ray alongside, the two Englishmen played their exhibition matches leading up to the Open as if the only real debate about the event was which of them would win.

For many readers, this story will be a sort of prequel to Chariots of Fire, the 1982 Best Picture Oscar winner. It takes place 11 years before the 1924 Olympics that formed the core of the movie’s story. Both this book and the movie are fascinating character studies of highly skilled athletes, with World War I in the background.

We can’t read about the 1913 Open without thinking about what would begin the next year. In Chariots, the millions of young men killed in the Great War are ever-present ghostly spectators as the young runners practice for their trip to Paris.

In addition, like Chariots one of this book’s central themes relates to the nature of amateur and professional sports when played at the highest levels of ability. Furthermore, both stories explore the developing symbiotic relationship between the media and sports.

Dealing with the competing demands of family ties and one’s chosen sport is another parallel element in the two stories. In Chariots Eric Liddell tries to balance the religious convictions that bring him to the ministry against those who see no need to limit the display of his awesome talents to every day but Sunday. Ouimet must contend with the deep disapproval of his father for even playing golf. His home’s proximity to The Country Club was critical to Ouimet’s development as a golfer, but it certainly didn’t smooth his fractious relationship with his father. In both cases, however, other strong family ties help both athletes cope.

(There is one other coincidence. The opening scene in Chariots, showing several dozen British runners along a beach, was filmed next to the first hole at St. Andrews’ Old Course.)

I can’t recommend this book highly enough.