Another good look at life on the Tour

August 24, 2007

There is very little that is really new in golf–only variations on what’s been done before.

Go to any well-stocked library and look at a stack of golf magazines. Nearly every swing tip found in a 2006 or 2007 magazine has been offered up as a brand new concept in some past decade’s issues.

The same is true for some kinds of golf books, including those promising to show the readers what it’s really like to play on the PGA Tour.

Within the last two decades there have been at least four of these treatments.

William Wartman’s Playing Through came out in 1990, recounting the highs and lows of the 1989 season. John Feinstein’s A Good Walk Spoiled studied a group of tour players during 1993 and 1994, making a long-running 1995 bestseller from what the subtitle called the “Days and Nights on the PGA Tour.” In 2002, Michael D’Antonio dipped a bit further in history for his Tour ’72, focusing on that remarkable year and featuring Nicklaus, Palmer, Player, and Trevino.

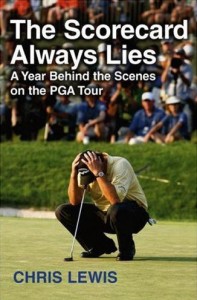

Chris Lewis’s The Scorecard Always Lies is the latest version, and it’s a pleasant addition to the genre (Free Press; $26.00 SRP).

As with his fellow chroniclers for their editions, Lewis discovered that golfers are among the most approachable professional athletes, even as the huge new money influx into the sport in the Tiger Woods era has brought them closer in annual earnings to other sports figures.

The fact that even with the huge new purses, most PGA Tour players aren’t quite up to the income potential of a journeyman second-baseman on a downmarket MLB team may have something to do with it. Even so, for all one reads about other athletes and their crippled relationship with most journalists, the golfers’ openness to media inquiries can still startle.

Not every pro athlete willingly admits that he ran barefoot into a tattoo parlor to escape a dicey late-night situation in a bad part of New Orleans. Nonetheless, Chris Couch talked about the incident, which just happened to take place a few days before he won the PGA Tournament that week at English Turn. Couch comes across as a pretty normal guy who just happens to play golf better than most, although his struggles with the short game will also sound familiar to the rest of us.

Lewis does a nice job in chatting up Tour golfers from a wide variety of age ranges. As with baseball, longtime participation at the highest levels remains a viable option for the highly-skilled willing to keep at it, unlike football and other sports that are less kind to older players. Pros in their 40s, such as Jeff Sluman and Mark Calcavecchia, provide a long view of their sport, while young players such as Geoff Ogilvy give some useful insights into the current state of the game.

In fact, Lewis’ coverage of Ogilvy and his contemporaries is perhaps the most interesting part of this year’s behind-the-scenes look at professional golf. It’s sometimes hard to appreciate the effect of the huge boost in earnings potential upon the sport, thanks largely to the world’s reaction to one very talented kid from southern California.

With so much new money on the table, the PGA Tour has vastly increased its ranks of international players such as Ogilvy, last year’s Open winner from Australia. Those kinds of winnings just aren’t available anywhere else, and money certainly talks a universal language in this sport.

As Lewis also shows, the boost in potential cash also affects the Tour players’ decisions about balancing their home lives with the roughly forty weeks of the traveling golf circus. They’re all independent contractors, so there’s no direct commitment to staying out on Tour as much as possible—but there’s all that money out there, too. This aspect of the sport is just as important in considering the changes in modern day professional golf as the technical advances made by the ball and club makers.

The fact that Lewis makes this point with a nicely conversational tone throughout the book is a pleasant bonus.