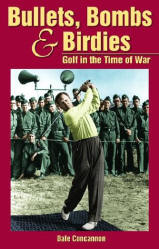

Bullets, Bombs & Birdies: Golf in the Time of War

The language of golf frequently uses war-like metaphors.

For example, long drives are bombed. Tournament players try to make the cut. Golf balls are struck. Golfers prone to losing their temper are sometimes said to have gone nuclear.

As Dale Concannon shows in this intriguing little study, golf’s connection to war extends far beyond the appropriation of the language of conflict. The sport became a primary contributor to the war effort in several countries, as a welcome relief for both military and civilians, and as a way to tap into patriotic fervor (and wallets, too).

The book’s stories are dominated by the two World Wars, but there is a short chapter or two outlining some of the golf/war connections that cropped up almost contemporaneously with the invention of the sport.

Concannon also points out how the sport’s previously limited appeal expanded with the Industrial Revolution and the rise of leisure time, primarily in Great Britain and the United States. During this period there were occasional associations between golf and war. For example, John Ball Jr., the double British Open and Amateur champion in 1890, also distinguished himself in the Boer War ten years later.

By the time of the First World War, the interplay between the sport and the war was much in evidence. The results of Concannon’s research should be illuminating to most readers. One chapter is devoted to the Niblick Brigade, a British Army outfit dominated by former golf professionals and their assistants.

The American contribution to victory in World War I was not limited to its industrial might and the Doughboys. American amateur golfers such as Bobby Jones and the leading professionals of the time, such as Walter Hagen, also helped raise huge sums in Liberty Bonds, with dozens of charity tournaments throughout the country. Concannon also gives several examples of how the USGA and other organizations dealt with the disruptions in their usual tournament schedules.

One chapter deals with golf and the Third Reich, an aspect of the game that was completely news to me. Karl Kenkell was the appointed leader of the Nazi attempts to use the sport for propaganda purposes, and his story was riveting.

The chapters dealing with World War II are also interesting, even as they cover far more familiar ground. Concannon presents a fairly complete picture of how golf was part of the civilian war effort. In addition, he describes how military prisoners of war also found ways to play golf as they waited for rescue.

The post-WWII chapters are fairly sparse, although there is a moving segment concerning Billy Casper and his morale-raising tour in Vietnam. A few photographs bring the reader current, concluding with a picture of a Marine hitting golf balls off an aircraft carrier on the way to Iraq.

The book includes several historic photographs and illustrations, including propaganda posters and cartoons.

Pieces of the story of golf and war have appeared in biographies of certain famous players, of course. Nonetheless, I don’t believe anyone has ever before given the issue its own book-length study. For that reason, Concannon has made an important contribution to the history of the game.

Review Date: March 14, 2003