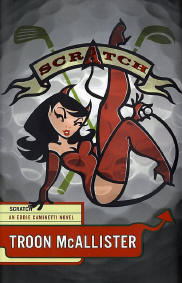

Scratch

I recently interviewed a golf shop salesman for a column about this year’s lines of golf clubs and golf balls.

During our chat I referred to that line about how companies such as Titleist, Taylor Made, and Calloway don’t actually sell equipment–they sell hope.

The salesman readily agreed. His livelihood depends on it, and the shop he works in does very well.

In Scratch, the great new addition to the Eddie Caminetti series, Troon McAllister shows how a remarkable amount of hype takes advantage of the touching, nearly childlike hopes of millions of golfers.

Caminetti himself is an otherworldly hustler, as shown in the very funny first two books about how he played golf (The Green and The Foursome). Therefore, it was probably only a matter of time before Caminetti turned his attention to the business side of the game, using his own special talents.

This time Caminetti has some help. A CalTech physicist named Norman Standish is recognized as a genius by his peers, but he knows that his work is nearly always based on detecting the flaws in others’ theories, rather than coming up with his own insights. He’s a bit depressed about it, and one of his buddies decides to cheer him up by making Standish part of a foursome for a round of golf.

It’s a Eureka moment.

At about the same time, Caminetti finds himself on the West Coast after a profitable stop at a poker parlor. (McAllister’s howlingly funny segment on this game cured me of any interest in ever trying my own hand at it.) The two men meet, and Standish is just persistent enough to break through Caminetti’s own suspicious nature.

The two men then combine their considerable talents to take on the golf ball industry, especially the folks at Medalist, the 800-pound gorilla of golf ball market share.

It’s not a fair fight. That’s why it’s so much fun to read about it.

For one thing, Caminetti and Standish use a form of marketing jujitsu in creating an incredible response to their new Scratch golf ball. Unlike Medalist, they don’t spend a dime buying the endorsements of touring pros. Unlike Medalist, they don’t flood the golf magazines and television with advertisements.

Instead, they use two basic techniques. First, a single golf pro begins using the ball, and startles everyone with his meteoric rise in the standings. It’s none other than Fat Albert Auberlain, Caminetti’s caddie during the Ryder Cup, in one of the nicely done bits of plot carryover from The Green.

Second, they price a dozen golf balls at an even $100, twice the amount charged by Medalist for its premium line of golf balls.

That’s about it. Boom goes the market. After all, if the Scratch balls cost that much, they must be really good. And besides, look at how that kid Auberlain is playing.

The stunning success of this new competitor drives the people at Medalist nuts. They try several schemes to restore their market share, but nothing seems to work. Every move they make is countered by more jujitsu from Caminetti and Standish.

Finally, the company president makes a fatal move. He sues the Scratch Company, picking the Augusta, Georgia Federal District Court for his forum.

Caminetti is nothing if not confident in his abilities. He decides to represent himself, with an attorney as an occasional assistant to help him over the procedural humps and bumps that usually trip up pro se litigants.

The trial itself is hilarious, at least from my perspective as an attorney. There’s just no way it could ever be conducted the way McAllister portrays it, but that doesn’t matter. It’s a satire, after all, and I’m not looking for slavish adherence to the mundane facts of federal court procedure.

I really liked the judge’s character, which reminded me a bit of the late Fred Gwynn’s brilliant portrayal in My Cousin Vinny.

One unlikely but comical courtroom event follows another, and the action then shifts to a round of golf at Augusta National. The company president thinks his long-time membership will give him an advantage. Somehow he forgets that Caminetti suggested the round as a way to settle the case, and what that means.

It was a mistake.

Once again McAllister shows how well he can describe a round of golf in which way too much thinking goes on.

One of the running subplots in the book also bears mentioning. At several places the conversation turns to why golfers love their game with such intensity. A wide range of theories are suggested and dismissed as incomplete.

As the book comes to a close, Caminetti finally offers up his own theory. It touches upon man’s characteristic search for signs of hope where he can, in a far broader context than the business of selling sporting goods that forms the basic plot of this entertaining novel.

Caminetti’s insight is well worth considering and adopting. It also shows that once again McAllister accomplished a primary goal of any good satire.

Review Date: March 30, 2003