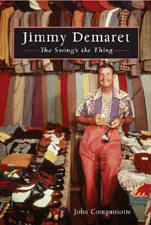

Jimmy Demaret: The Swing’s the Thing

Walter Hagen was a brilliant marketer as well as a great golfer.

He is generally recognized as one of the first professional golfers to understand and exploit the power of the media in building a larger fan base for his sport. Hagen’s devil-may-care, high-living attitude fit perfectly in the Roaring Twenties. The fact that Sir Walter was also one of the best players the sport has ever seen certainly didn’t hurt, either.

Jimmy Demaret understood what Hagen was doing with his on- and off-course publicity efforts, and took to much the same behavior like a duck to water.

In many respects Demaret became the next-generation Hagen. He maintained a popular, perpetually sunny attitude while playing at the highest levels. He had a warm relationship with regular fans as well as celebrities such as Bob Hope and Bing Crosby. And, of course, today Demaret may be best remembered for his remarkably vibrant choices in golf fashion, going well beyond Hagen’s own notable style.

Demaret was also one of those professional athletes that continually amaze those who only look at the surface. For all his apparent nonchalance, the Texan could flat out play. He won 31 victories on the PGA Tour during a time when his competition included Hogan, Snead, Nelson, and many others now with Demaret in the Golf Hall of Fame. His three Masters wins put Demaret in rare company. His 6-0 record in the Ryder Cup is far better than most of those who have had the honor to compete in that tournament.

Demaret also began where Hagen left off when it came to promoting golf and doing well for himself at the same time. He signed onto a wide variety of endorsement contracts, leveraging his tour winnings into side businesses that paid far better than the modest Tour purses at the time. He was one of the first professional golfers to be a success as a broadcaster, especially during his years on Shell’s Wonderful World of Golf series. Along with Jack Burke, Jr., Demaret designed and built the Champions Golf course in Houston, and was one of the creators of what is now known as the Champions Tour.

With all that Demaret accomplished during his life, one would think that a very good biography could be written about him.

After reading this book, however, I must regretfully suggest that particular goal remains to be achieved.

It’s obvious that the author, John Companiotte, had good access to a wealth of materials for his research. He interviewed several people who knew Demaret intimately. In addition, he quotes liberally from a wide range of publications in fleshing out the details of Demaret’s life.

On the other hand, there’s just too much repetition of the same material. Within two pages, for example, Companiotte repeats an anecdote about a double-date Demaret once had with Dave Marr’s father. The same story shows up again later in the book.

There were several other odd editing choices. For example, the reader does not learn until the end of the book that Demaret’s family nickname was Newt, a contraction of his middle name. One would think that kind of detail would be mentioned at the beginning of the book, dealing with Demaret’s growing years. In addition, in two consecutive sentences Companiotte first writes about “pursuing a career as a tournament golfer,” and in the next sentence discussed “pursuing victories in professional events at the time.”

These mistakes aren’t mortal sins, of course. Nonetheless, these and other examples are simply jarring.

I fully appreciate the hard work involved in compiling the information needed for a sports biography, and it’s clear that Companiotte did a good job on that part of his task. For example, the photographs sprinkled throughout the book give an interesting glimpse of Demaret and his era. On the other hand, on far too many occasions the writing is workmanlike at best, and frankly dull in other spots.

This book could have been much better. It needed a good editor, ruthless with the red pen and willing to force several more rewrites to make the copy be as lively as the subject.

This book is valuable for its contribution to golf history. Unfortunately, however, it’s just not very well written.

Review date: April 4, 2004