Course and player management skills focus of new book

July 23, 2010

Like most golfers who were first exposed to the sport in the last few decades, I have almost never played a round with the assistance of a real, live caddie.

On the rare occasions that I did, at Pebble Beach Golf Links and The Links at Spanish Bay, they were great experiences.

I had no idea how liberating it was to simply walk the course without a bag on my shoulders, or while pushing or pulling a golf trolley. All I had to do was think about my next shot, and listen to what the caddie suggested about club selection, targeting, and how my putt would probably break on the green.

The loopers I hired clearly had years of experience, both on the courses and with a wide variety of golfers. Their people skills were the equal of their ability to gauge the wind, pick a club, and read a green.

Whenever they’re done caddying, some of these guys should explore a career in the diplomatic service.

The caddie/player teams we see on the professional tours are just one of the many ways in which the professional game differs so much from the rest of us. The caddie can help process the flow of information that is needed to put the right swing on the ball, and also keep the golfer maintain a focus on the task at hand.

Left to our own devices, too many of us can ruefully admit to thinking about the last shot while in the middle of the next one, with less than happy results.

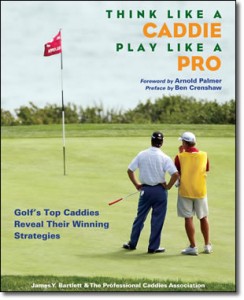

Although caddies are rare commodities, the rest of us can still take advantage of what caddies can bring to the game, if we really want to. That’s the message of James Y. Bartlett’s new book, Think Like a Caddie, Play Like a Pro” (Sellers Publishing; $24.95 SRP). Bartlett is a longtime golf writer, and teamed up with the Professional Caddies Association to write this book.

Other contributors include Reid Champagne, who writes for Delaware Today magazine and other local publications, as well as Mark Nelson and Anderson Craigg.

Caddies don’t make the swings, but they can help the golfer with everything that leads up to them. The point of the book is to suggest to players how to use the resources that any good caddie brings to a round; in a sense, how to be a caddie for yourself.

Think in terms of the typical situation facing any golfer in a routine eighteen-hole round. A good caddie will know the course conditions. The caddie will help the golfer assess every likely element that could affect the ball’s flight or roll toward the target, be it wind, ground slope, hazards, or other factors.

A caddie will rarely if ever let the golfer take his swing without making sure the player is aware of these factors, is prepared to handle them, and is focused only on that particular shot at that particular time.

A professional player can take advantage of a second brain in conducting the pre-shot routine. What this book does is illustrate how the rest of us should try to split our minds in two and improve our results with the same process.

The book includes plenty of examples from the professional tours, along with several amusing anecdotes. There are several useful checklists for different game situations.

I also especially liked a segment on the right kind of statistics to keep track of during a round. Some of these stats don’t normally show up on The Golf Channel’s post-tournament shows, but they should be highly useful for the rest of us.

This book is a nice introduction to the concepts of course and player management that are such important elements to improving your game. It is a fast and enjoyable read, written from an interesting perspective.